By Carl Hart @drcarlhart

In the past, I avoided speaking about my research publicly because it is potentially controversial. Some may, for example, describe me as a “taxpayer-funded drug pusher, giving ‘crackheads’ what they want.” Others may question the ethics of giving crack cocaine for research purposes. Over the course of my career, however, I have come to the conclusion that it would be unethical not to conduct this type of research because it provides a wealth of information about the real effects of crack cocaine and the findings have important implications for public policy and the treatment of cocaine addiction.

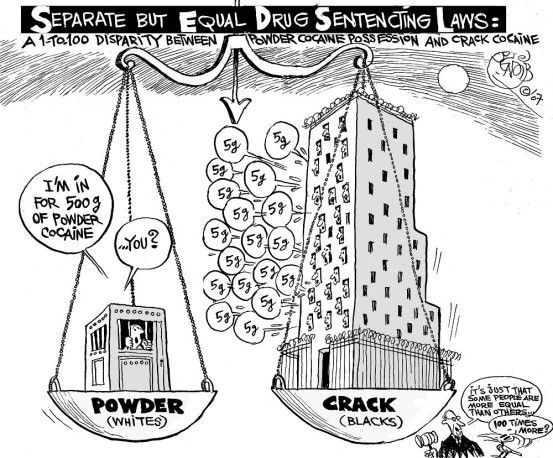

Two recent developments deemed as considerable progress toward enhancing racial justice force me now to speak out about my research on crack cocaine. The first development was the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010, which decreased, but did not eliminate, the sentencing disparity between crack cocaine and powder cocaine offenses. The second was the recent Supreme Court ruling that the Fair Sentencing Act will also apply to people whose offenses occurred before the law was passed but were sentenced after it passed.

Before explaining why I believe these developments are insufficient, I need to provide a brief history of how we got here. In 1986, Congress passed the Anti-Drug Abuse Act, which stated that a person convicted of selling 5 grams of crack cocaine was required to serve a minimum sentence of 5 years in prison. To receive the same sentence for trafficking in powder cocaine, an individual needed to possess 500 grams of cocaine — 100 times the crack cocaine amount.

At the time, crack cocaine was believed to be so powerfully addictive that even first-time users would become addicted. It had also been linked to the deaths of two promising young athletes — Len Bias and Don Rogers — although later it became clear that the athletes had taken powder and not crack cocaine. Nonetheless, there remained a public perception that crack cocaine produced unpredictable and deadly effects. By 1988, concern about the drug had increased so much that penalties of the 1986 law were extended to persons convicted of simple possession, even first-time offenders. Simple possession of any other illicit drug, including powder cocaine or heroin, by a first-time offender carried a maximum penalty of one year in prison.

When the furor about crack cocaine had settled, some began raising concerns that crack/powder laws disproportionately targeted blacks. A whopping 85% of those sentenced for crack cocaine offenses are black, despite the fact that the majority of users of the drug are white. Even presidential candidate Barack Obama voiced strong concerns, “…let’s not make the punishment for crack cocaine that much more severe than the punishment for powder cocaine when the real difference between the two is the skin color of the people using them…That will end when I am president.” On August 3, 2010, President Obama signed the Fair Sentencing Act into law, reducing the sentencing disparity between powder and crack cocaine from 100:1 to 18:1. And on June 21, 2012, the highest court ruled that the new law can be applied retroactively, but only for those who were sentenced after the law was passed.

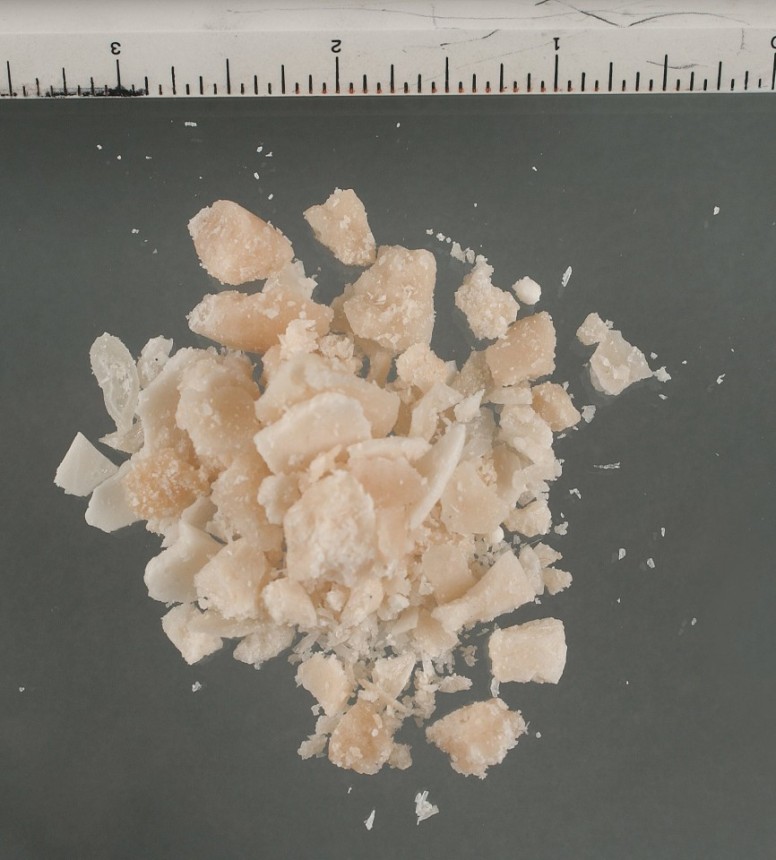

So why isn’t this real progress? From a scientific perspective, any sentencing disparity for crack and powder cocaine makes no sense. Based on my studies with all forms of cocaine, there are no pharmacological differences between crack and powder cocaine to justify their differential treatment under the law. Both forms of cocaine produce identical effects; these effects are predictable. That is, as the dose is increased, so are the effects, whether they are blood pressure and heart rate OR subjective “high” and addictive potential. The way the drug is taken differs based on its form, however. Crack is smoked, whereas powder is swallowed, snorted, or injected. More intense effects are observed when the drug is smoked or injected, but the drug itself remains the same. To punish crack offenses more harshly than powder offenses is like punishing more harshly those who are caught smoking marijuana than those caught eating marijuana-laced brownies.

Not only have I learned valuable information about cocaine itself, but I have also learned that much of what we think we know about crack cocaine users is wrong. A common misconception is that virtually all users of the drug are addicted. This is simply inaccurate. The overwhelming majority of users use the drug without problems. This is not to condone cocaine use or encourage illegal activity. I am simply stating the facts. Another persistent stereotype is that most crack cocaine users are impulsive, focused only on getting another hit of the drug. Demanding schedules are imposed on research participants in my studies; they are required to do considerable planning, inhibit behaviors (e.g., drug use) that may be inconsistent with meeting study schedule requirements, and delay immediate gratification. Most meet these demands with no problems.

In 1964, when asked whether the U.S. had made sufficient progress towards racial equality, Malcolm X said “If you stick a knife in my back nine inches and pull it out six inches, there is no progress… The progress is healing the wound.” Accordingly, I think it’s time for us to eliminate the sentencing differences and apply this change retroactively to all crack cocaine offenders. Such changes would be in line with the scientific evidence and the ethical thing to do. More importantly, it would be a significant and honest step toward healing the wounds of racial injustice.