By Matt Sledge

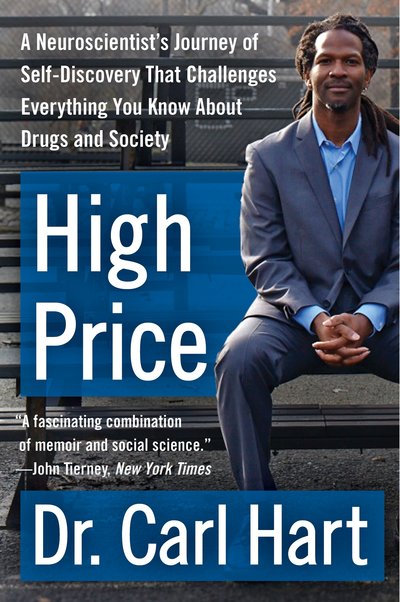

[dropcap]C[/dropcap]Carl Hart wants drug policy to go where science takes it. The rest of us may not be so ready. The 46-year-old associate professor at Columbia University is out next month with a new book called High Price.

That long title covers the two sides of Hart’s claim to special insight on drugs: his early life growing up in the roughest neighborhoods of Miami, and his remarkable transformation into a researcher upending long-received wisdom about substance use and abuse.

Everything we’ve been told about drugs is wrong, Hart says. The vast majority of drug users never become addicted. Cops, politicians and the media have consistently told us scary stories overstating the effects of drugs, misinterpreting the science around them in the process.

Hart’s own research is notable for focusing on drugs administered to humans, not rats, in a lab. It has cut against the prevailing conventional wisdom that, for example, crack-cocaine users don’t respond to economic alternatives. He serves on the highest body in his field, the National Advisory Council on Drug Abuse, which is affiliated with the National Institutes of Health.

Meeting up with The Huffington Post in a Manhattan coffee shop on a recent Friday afternoon, Hart’s style is casual. Clad in a bright T-shirt and toting big headphones, his answers to questions ranging from drug policy to race are blunt. For Hart, writing this book seems to have been an exercise in liberation.

[pullquote type=”right”]“If drugs are bad, any respectable society should do something to deal with them. And our society has decided that what we will do is we will get rid of certain drugs at all cost, and the costs are borne by poor people,” he says. “Drugs are not bad; that’s bullshit.”[/pullquote]”I’m the co-author of a textbook that does that [dry approach]. It’s the No. 1 selling book at the college level about drugs. It hasn’t had any impact,” he says. “So I wanted a book that people who are not taking this class would read and find interesting. … Of course that was frightening, too, putting yourself out there. But I didn’t know any other way to do it.”

One of eight kids, Hart watched as his father beat his mother and his family wound up living off welfare in housing projects. He tells of his own history with drugs like marijuana — both using and selling — and of the surprise discovery that he was the father of a child, Tobias. His son was 21 when they first met and had fallen into a life slinging on the streets. Hart says that might have too easily have been his fate as well, had the Air Force not offered him a way out.

All of that is in the book. Hart knows his book may provoke reactions from both his family and the academy when it’s released. He already believes that he has lost research grants because of his outspoken advocacy for reform with the Drug Policy Alliance. The book and a recent appearance in the 2012 documentary film “The House I Live In” will only increase the scrutiny of his work.

But it’s time, Hart says, “to set the record straight.” Ultimately, he would like the United States to decriminalize all drugs, along the lines of a similar, widely-praised effort in Portugal.

“If drugs are bad, any respectable society should do something to deal with them. And our society has decided that what we will do is we will get rid of certain drugs at all cost, and the costs are borne by poor people,” he says. “Drugs are not bad; that’s bullshit.”

Why did you want to write the book?

You’re dealing with this important subject, and you’re not dealing with the obvious elephant in the room: Are drugs good, are drugs bad, do these cause all these effects that people say? Because if they do, then you probably should be taking the approach that we take. But the problem is that they don’t. When you really look at the data, you see that most people who use drugs don’t have a problem with them. Some even become president: Barack Obama, George Bush, Bill Clinton — all of these folks have used these drugs.

So do you have an answer to that question, are drugs good or are drugs bad?

The answer to that question is neither. That’s like saying are automobiles good or bad. They certainly can be useful if you need to go some distance in a short period of time. But they can also be problematic if you are irresponsible in your operating of them. The same is true of drugs.

You’ve used marijuana, you’ve used cocaine. Sometimes in the debate over drugs, even people on the drug reform side are pretty reluctant to own up to their own past use. I think they perceive it as somehow delegitimizing their arguments. Are you worried that could happen because you are so frank?

I certainly was worried about that early in my career, very worried about that. Now I’m less worried because I challenge anybody to know more about drugs than me. This is after years of having worked, and now I’m comfortable [with] who I am. But we really need people to get out of the closet, because as long as people are allowed to be in the closet, the caricature of the drug user is this irresponsible troublemaker. And as long as you have that be the face of drug use, the society feels it has to do stuff, and I agree with them.

What is the norm within the fields of pharmacology and neuroscience — do people talk about their own drug use?

The researchers who used to study this in the 1960s and 1970s certainly did.

And that did delegitimize them, in some people’s eyes at least.

Great point. It deligitimized them — only if you were Timothy Leary, mainly. He was a horrible scientist, that’s number one, but there were good scientists who were doing this stuff and they were not so delegitimized. … As the generations changed, the new generations became scientists in this area, then they actually believed the bullshit. There are a number of young scientists who are afraid of these drugs, and they’ve never used, and they don’t know anything about these drugs besides what they see on TV, or in their rats.

Do you have to use drugs to be a good scientist?

No, absolutely not. You have to be open-minded and you have to be critical, and you have to let go of your predispositions about what you’ve been told that doesn’t have foundations in evidence.

Has your funding ever been threatened because you don’t buy into “the hysteria game”?

I had two huge grants, multimillion dollar grants. They run out, and I can’t get funded anymore. I wrote a really good grant recently — I’ll keep trying. I’ve been doing this book now, but one of the critiques of my last proposal was “what are you trying to do, show that drugs are good?” And it had nothing to do with that, but I think yeah, I think that people are suspicious of me.

Is that stymieing your science right now?

Oh yeah, absolutely. You don’t have money, you can’t do science. But that’s part of the price that I pay.

What would you like to research, given an unlimited budget?

I’d like to do a study that compared the cognitive performance in brain imaging of [New York Police Department officers] with some methamphetamine addicts, with some crack addicts, and we’ll see that our drug users will outperform the cops on many of the measures.

[magicactionbox] Are there police whose voices you respect on this issue — cops we should listen to?

No. Why should we? When we talk about drugs, I’m thinking about the assumptions that we made in order to regulate them the way we do. And the assumptions that we made are almost all biological and pharmacological, and so to ask the cop is stupid in my view. Cops are paid to go after criminals, that’s it, and we have defined these guys as criminals.

How influential can shifting attitudes towards marijuana be when it comes to other drugs? I think there’s a certain perception among a lot of people that marijuana’s just different from all the hard stuff. So when Colorado and Washington legalize marijuana, does that necessarily mean that people are going to maybe look at the science a little more when it comes to other drugs, like cocaine?

Hell no. And that’s a problem, it’s a problem I have with the marijuana sort-of-legalizers and those people, because they have done harm as well by trying to separate marijuana from those other drugs, and they look down on those other drugs, which is a mistake. So when people want to say we should decriminalize marijuana, no — we should decriminalize everything, heroin included.

Are there any politicians who are doing it right?

[Former Democratic Virginia Senator] Jim Webb would listen, but I don’t think he was that courageous, although people give him a lot of credit for being so. I’ve talked to him and he’s just said point blank: ‘Look man, I represent some conservatives in Virginia and I’m not doing that.’ I get it, I understand the difficult spot those politicians are in; they need to get voted in. I get it. That’s why my book is not aimed for politicians. My book is for the people. Fuck the politicians; I’m done with them.

Is there any drug that does scare you?

Marijuana scares me, alcohol scares me — they all do. Marijuana — I just don’t get it. It’s not that good, and then it has these potential negative consequences. There are far better drugs, and I just don’t get — I think that people do it because of the chicness or the forbidden-fruit bullshit. Heroin is a much better drug; methamphetamine is a much better drug. But if you have to go to work the next day and get some sleep it’s not, so cocaine would be a better drug. There are so many better drugs.

So yeah, a lot of them scare me if they are used inappropriately or improperly, but there isn’t one drug where I wouldn’t tell my kid, ‘Don’t use this drug.’ But the adulterants that people cut drugs with, those I worry about a lot, and my kids are fully aware of what drugs are cut with, rather than the drugs themselves.

How old are they now, your kids?

18 and 12. And we’ve been having conversations —

So it’s a live issue.

Oh yeah. We’ve been having these conversations since they were 5. They’ve seen me give drugs in the lab and those kinds of things, so their drug education is outstanding and I don’t worry about them because I know if they do indulge, they know what they’re doing.

One of the things I was astounded to read in the book — and I guess I shouldn’t be — is that you said in the year you got your PhD, you were the only black, male neuroscience PhD.

I don’t know if it’s more a reflection of science or a reflection of society. When we think about my peers, many of them have criminal records because of the war on drugs. So this is happening before science; this is stuff that’s happening with our drug policy and the way we think about race in this society. I’m the only tenured black faculty in the sciences at Columbia, in the middle of Harlem. This is about society. It has little to do with science.

How would science be better with more diversity?

You just have these different perspectives that are informed that are not from our typical pool of scientists, and so you look at problems differently. You are certainly more courageous in some areas because you see the impact on people you care about. Whereas other folks don’t have to see the impact, and so they’re just unaware.

If people come away with one thing from your book, what should it be?

I would hope they seriously look at the way we are regulating drugs and punishing people, and I hope they come away thinking this is so unfair and this is so un-American. … They [can] say it’s unfair and now they have science, evidence to support it and not just somebody tugging at their heart, but they have somebody tugging at their head as well.

An older version of this post appears in HUFFPOST