The waiting area of the Brooklyn Family Courthouse isn’t where you’d expect to find a Columbia University neuroscientist. But Carl Hart isn’t your average professor.

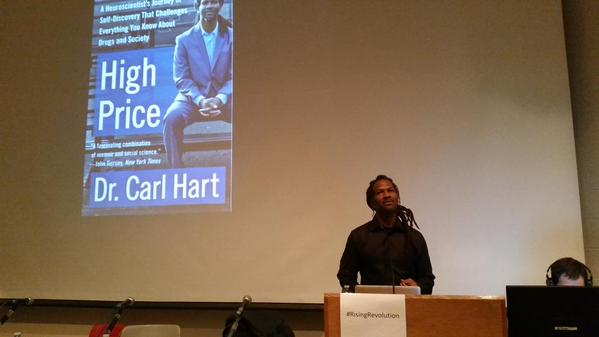

His credentials are sterling: Hart has studied addiction and the brain for the last 25 years. He has tenure in Columbia’s Psychology Department. He’s on the National Advisory Council for Drug Abuse. His book, High Price, questions the War on Drugs. But his insistence on using lab research to advocate for changes in how drugs are dealt with in courts like this one is what makes him stand out.

“Drugs are not as dangerous as we have made them out to be,” Hart says. “I’m trying to get people to use the data, the empirical evidence, and when you do that, you realize that we have been lied to, the public has been lied to.”

Professor Hart has been taking the stand and submitting written testimony in family courtrooms around the city, advocating for children to stay with their parents, even if their parents have tested positive for using marijuana.

Hart says the belief that casual marijuana use impairs your parenting has no scientific basis — and pot use that isn’t excessive is on par with having a drink now and again: “We don’t remove children because their parents drink alcohol,” Hart points out. “My kids would be removed if that was the case.”

His journey from the lab to the courtroom is as much personal as it is scientific. Hart grew up in a Miami housing project — where drugs were impossible to avoid. He even sold some marijuana in high school. But by the time he got to college, his interest in drugs wasn’t recreational — it was clinical.

He started out studying how rats react to morphine, gradually working up to studying human drug users under carefully controlled, laboratory conditions.

The year he received his doctorate, he was the only black PhD in neuroscience in the country. And while he began studying drugs thinking his work would help him understand the chaos of his upbringing, he found that even the hardest drugs defied his expectations.

Take crack: “We’ve given thousands of doses of crack cocaine in the lab and haven’t seen any negative effects,” Hart says.

And marijuana seemed relatively harmless — far less addictive than nicotine or alcohol. He insists even long-term users don’t necessarily see memory damage: “When you look at the data carefully, there aren’t any consequences of marijuana use that is not excessive,” he says.

But for friends and family in his old neighborhood – drugs did have consequences.

“More than 50 percent of the guys who I grew up with spent time in jail on some drug-related charge,” Hart says. “It’s always some minor trafficking or possession charge. It’s so normalized.”

That discrepancy between his conclusions in the lab and the consequences at home has made him a firm believer in decriminalization for all drugs.

But that’s a controversial opinion for an Ivy League researcher. Just down the hall from Hart’s uptown lab is the man who hired him, Dr. Herb Kleber. Kleber looks at the same data on addiction and sees substances that are dangerous – and he’s not alone.

“I would say the majority of scientists would agree with me,” Kleber says.

Dr. Kleber was the deputy drug czar under the first President Bush. He sees marijuana laws loosening around the country — and says the consequences will be scary.

“I don’t think legalization is the answer,” he continues. “We don’t want to lose a generation by making these drugs more readily available.”

For Hart, seeing the way the law plays out in places like Brooklyn’s Family Court disturbs him. The last time he testified, it was on behalf of a mother who had tested positive for marijuana while giving birth in a city hospital. She said she used pot during prayer — and her children had never seen her intoxicated.

But the city investigated her for negligence anyway. Hart says even the case worker was torn: “She wanted me to know that she was in agreement with me, but had to do her job and wanted me to know that she was a good person,” Hart recalls. “I wasn’t her God — but she wanted forgiveness.”

The charges against that mother were eventually dropped. And if Professor Hart can use his research to change the outcomes for other moms like her, he will.